Bibliography

Primary Sources

Guy de Lusignan, King of Jerusalem, Letter to the Archbishop of Canterbury, in The Conquest of Jerusalem and the Third Crusade: Sources in Translation, ed. and trans. Edbury P., (Aldershot, 1988), pp.168-169

Ambroise, The History of the Holy War: Ambroise’s Estoire de la guerre sainte, ed. Ailes M. and Barber M., trans. Ailes M., (Woodbridge Suffolk, 2003)

Bahā’ al-Dīn Ibn Shaddād, The Rare and Excellent History of Saladin, trans. Richards D.S., (Aldershot, 2001)

Henry II, King of England, The Saladin Tithe, 1188, in Select Charters of English Constitutional History, ed. Stubbs W., (Oxford, 1913), p. 189; reprinted in Cave R.C. and Coulson H.H., A Source Book for Medieval Economic History, (New York, 1965), pp. 387-388, athttp://legacy.fordham.edu/halsall/source/1188Saldtith.asp, accessed on 14/03/2015

Ibn al-Athīr, al-Kāmil fī’-ta’rīkh; Part 2; The Years 541-589/1146-1193; The Age of Nur al-Din and Saladin , trans. Richards D.S., (Aldershot, 2007)

Itenerarium Peregrinorum et Gesta Regis Ricardi, trans. Nicholson H., (Aldershot, 1997)

Richard I, King of England, Letter to the Abbot of Clairvaux, in The Conquest of Jerusalem and the Third Crusade: Sources in Translation, ed. and trans. Edbury P., (Aldershot, 1988), pp.179-181

Richard of Devizes, Chronicon, ed. and trans. Appleby J.T., (London, 1963)

Roger de Hoveden, The Annals of Roger de Hoveden: Comprising the History of England and of Other Countries of Europe Vol.2, trans. Riley H.T., (Felinfach, 1997)

Secondary Sources

Asbridge T., The Crusades; The War for the Holy Land, (London, 2012)

Asbridge T., The Crusades; The War for the Holy Land, (London, 2012)

Barber M., The New Knighthood; A History of the Order of the Temple, (Cambridge, 2000)

Flori J., Richard the Lionheart; King and Knight, trans. Birrell J., (Edinburgh, 1999)

Gillingham J., Richard I, (New Haven and London, 2002)

Lord E., The Knights Templar in Britain, (Harlow, 2004)

Nicholson H., A Brief History of the Knights Templar, (London, 2010)

Phillips J., Holy Warriors: A Modern History of the Crusades, (London, 2010)

Rogers R., Latin Siege Warfare in the Twelfth Century, (Oxford, 1992)

Smail R.C., Crusading Warfare, 1097-1193, (Cambridge, 1995)

Turner R.V. and Heiser R.R., The Reign of Richard Lionheart Ruler of the Angevin Empire, 1189-99, (Harlow, 2005)

Tyerman C., England and the Crusades, 1095-1588, (Chicago and London, 1988)

End Notes

[1]Philips J., Holy Warriors: A Modern History of the Crusades, (London, 2010) p.164

[1]Philips J., Holy Warriors: A Modern History of the Crusades, (London, 2010) p.164

[2]Barber M., The New Knighthood: A History of the Order of the Temple, (Cambridge, 2000) p.120

[3]Nicholson H., A Brief History of the Knights Templar, (London, 2010), p.80

[4]Barber M., The New Knighthood, p.119

[5]Ibn al-Athīr, al-Kāmil fī’-ta’rīkh; Part 2; The Years 541-589/1146-1193; The Age of Nur al-Din and Saladin , trans. Richards D.S., (Aldershot, 2007), p.367-8

[6]Itenerarium Peregrinorum et Gesta Regis Ricardi, trans. Nicholson H., (Aldershot, 1997), p.209

[7]Bahā’ al-Dīn Ibn Shaddād, The Rare and Excellent History of Saladin, trans. Richards D.S., (Aldershot, 2001), p.147

Ibid p.123

[8] Ibn al-Athīr, al-Kāmil fī’-ta’rīkh, trans. Richards D.S., p.387

[9] Roger de Hoveden, The Annals of Roger de Hoveden: Comprising the History of England and of Other Countries of Europe Vol.2, trans. Riley H.T., (Felinfach, 1997), p.210

[10]Itenerarium Peregrinorum, trans. Nicholson H., p.79

[11]Ibn al-Athīr, al-Kāmil fī’-ta’rīkh, trans. Richards D.S., p.367-368

[12]Itenerarium Peregrinorum, trans. Nicholson H., p.78

[13]Richard of Devizes, Chronicon, ed. and trans. Appleby J.T., (London, 1963), p.39

Rogers R., Latin Siege Warfare in the Twelfth Century, (Oxford, 1992), p.234

[14]Ambroise, The History of the Holy War: Ambroise’s Estoire de la guerre sainte, ed. Ailes M. and Barber M., trans. Ailes M., (Woodbridge Suffolk, 2003), p.119

[15]Itenerarium Peregrinorum, trans. Nicholson H., p.253-4

Ambroise, The History of the Holy War, trans. Ailes M., p.119

Ibid p.120

[16]Asbridge T., The Crusades; The War for the Holy Land, (London, 2012), p.475

Richard I, King of England, Letter to the Abbot of Clairvaux, in The Conquest of Jerusalem and the Third Crusade: Sources in Translation, ed. and trans. Edbury P., (Aldershot, 1988), pp.179-81, p.180

[17] Flori J., Richard the Lionheart; King and Knight, trans. Birrell J., (Edinburgh, 1999), p.138

[18]Smail R.C., Crusading Warfare, 1097-1193, (Cambridge, 1995), p.164

[19]Itenerarium Peregrinorum, trans. Nicholson H., p.269

[20]Barber M., The New Knighthood, p.117

[21]Henry II, King of England, The Saladin Tithe, 1188, in Select Charters of English Constitutional History, ed. Stubbs W., (Oxford, 1913), p. 189; reprinted in Cave R.C. and Coulson H.H., A Source Book for Medieval Economic History, (New York, 1965), pp. 387-388, athttp://legacy.fordham.edu/halsall/source/1188Saldtith.asp, accessed on 14/03/2015

Guy de Lusignan, King of Jerusalem, Letter to the Archbishop of Canterbury, in The Conquest of Jerusalem and the Third Crusade: Sources in Translation, ed. and trans. Edbury P., (Aldershot, 1988), pp.168-169, p.169

[22]Itenerarium Peregrinorum, trans. Nicholson H., p.280

[23]Ibid.

[24]Gillingham J., Richard I, (New Haven and London, 2002), p.182

[25]Itenerarium Peregrinorum, trans. Nicholson H., p.280

[26]Bahā’ al-Dīn Ibn Shaddād, The Rare and Excellent History of Saladin, trans. Richards D.S., p.98

[27]Ibn al-Athīr, al-Kāmil fī’-ta’rīkh, trans. Richards D.S., p.365

[28]Richard I, King of England, Letter to the Abbot of Clairvaux, in The Conquest of Jerusalem and the Third Crusade: Sources in Translation, ed. and trans. Edbury P., p.181

Asbridge T., The Crusades; The War for the Holy Land, p.494

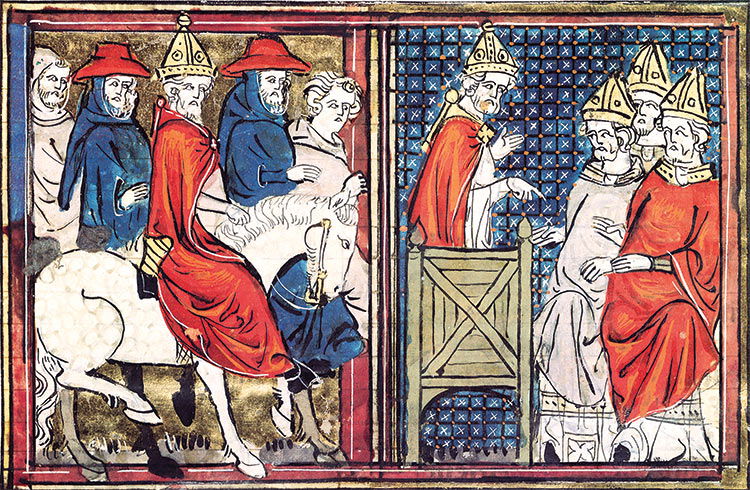

The Council of Clermont and the arrival of Pope Urban II. Bibliothèque Nationale / Bridgeman Images

The Council of Clermont and the arrival of Pope Urban II. Bibliothèque Nationale / Bridgeman Images Crusaders embark for the Levant. From 'Le Roman de Godefroi de Bouillon', France, 1337. Bibliothèque Nationale / Bridgeman ImagesThe reaction to Urban's appeal was astounding and news of the expedition rippled across much of the Latin West. Thousands saw this as a new way to attain salvation and to avoid the consequences of their sinful lives. Yet aspirations of honour, adventure, financial gain and, for a very small number, land (in the event, most of the First Crusaders returned home after the expedition ended) may well have figured, too. While churchmen frowned upon worldly motives because they believed that such sinful aims would incur God's displeasure, many laymen had little difficulty in accommodating these alongside their religiosity. Thus Stephen of Blois, one of the senior men on the campaign, could write home to his wife, Adela of Blois (daughter of William the Conqueror), that he had been given valuable gifts and honours by the emperor and that he now had twice as much gold, silver and other riches as when he left the West. People of all social ranks (except kings) joined the First Crusade, although an initial rush of ill-disciplined zealots sparked an horrific outbreak of antisemitism, especially in the Rhineland, as they sought to finance their expedition by taking Jewish money and to attack a group perceived as the enemies of Christ in their own lands. These contingents, known as the 'Peoples' Crusade', caused real problems outside Constantinople, before Alexios ushered them over the Bosporus and into Asia Minor, where the Seljuk Turks destroyed them.

Crusaders embark for the Levant. From 'Le Roman de Godefroi de Bouillon', France, 1337. Bibliothèque Nationale / Bridgeman ImagesThe reaction to Urban's appeal was astounding and news of the expedition rippled across much of the Latin West. Thousands saw this as a new way to attain salvation and to avoid the consequences of their sinful lives. Yet aspirations of honour, adventure, financial gain and, for a very small number, land (in the event, most of the First Crusaders returned home after the expedition ended) may well have figured, too. While churchmen frowned upon worldly motives because they believed that such sinful aims would incur God's displeasure, many laymen had little difficulty in accommodating these alongside their religiosity. Thus Stephen of Blois, one of the senior men on the campaign, could write home to his wife, Adela of Blois (daughter of William the Conqueror), that he had been given valuable gifts and honours by the emperor and that he now had twice as much gold, silver and other riches as when he left the West. People of all social ranks (except kings) joined the First Crusade, although an initial rush of ill-disciplined zealots sparked an horrific outbreak of antisemitism, especially in the Rhineland, as they sought to finance their expedition by taking Jewish money and to attack a group perceived as the enemies of Christ in their own lands. These contingents, known as the 'Peoples' Crusade', caused real problems outside Constantinople, before Alexios ushered them over the Bosporus and into Asia Minor, where the Seljuk Turks destroyed them.

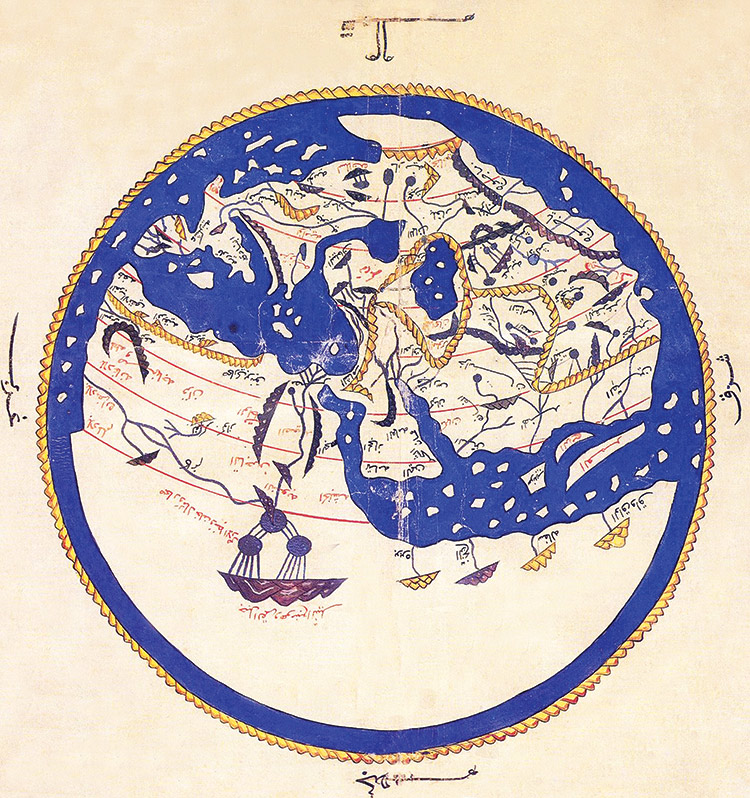

Muhammad al-Idrisi's map of the world, with Jerusalem at its centre, drawn for Roger II of Sicily in 1154. Bridgeman Images

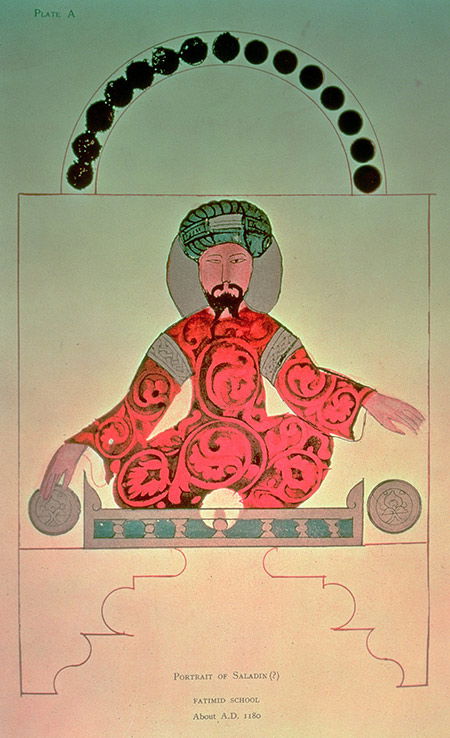

Muhammad al-Idrisi's map of the world, with Jerusalem at its centre, drawn for Roger II of Sicily in 1154. Bridgeman Images Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem, reconsecrated as an Islamic shrine when Jerusalem was retaken by Saladin in 1187. Jonathan Phillips

Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem, reconsecrated as an Islamic shrine when Jerusalem was retaken by Saladin in 1187. Jonathan Phillips

Capture of Constantinople by the Fourth Crusade in 1204

Capture of Constantinople by the Fourth Crusade in 1204

Modern painting of Mehmed II and the Ottoman Army approaching Constantinople with a giant bombard, by Fausto Zonaro

Modern painting of Mehmed II and the Ottoman Army approaching Constantinople with a giant bombard, by Fausto Zonaro